We don’t belong to the same boat

It’s the storm we share

We all belong to the one road

It’s up to you to get there

- Tonnta, Amble

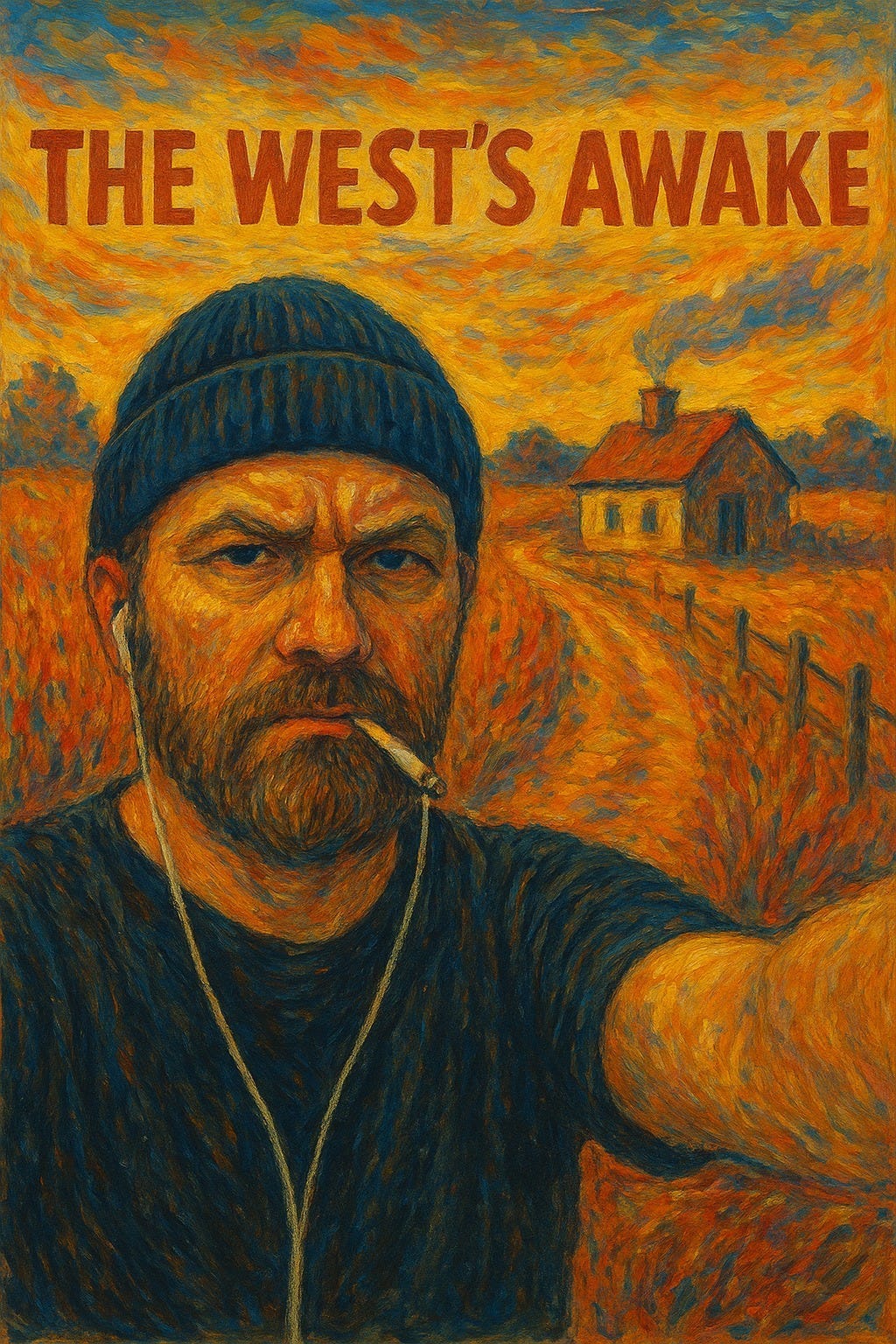

I catch glimpses of John staring silently back at me from the mirror—the older I get. Smiling that bashful, innocent smile of his and puffing away on a filterless Sweet Afton. A bachelor—he grew older as we grew up in the home-house, more brother than uncle.

The nineteen-eighties description of him would’ve been that he was odd, with the poor nerves at him the whole time. Chain-smoking cigarettes and drinking endless streams of sugared tea. Quiet as a church mouse. I note that I chain-smoke, drink from the same stream of sugared tea and haven’t been saying too much lately. He smiles, winks back at me from the mirror, and puts the spare hand out to cadge a fag for later, God rest him.

The nineteen-nineties medicated the poetry of oddness and nerves into the soulless phrases of the science wizards, and so terms like paranoid schizophrenia began popping up in conversation. Injecting tranquilised stillness while gradually removing the life force from behind his beautiful blue eyes, bit by bit.

He was an angel, of course, but as my mother would comment, you needed to be a feckin’ martyr to live with him. I am tempted to say he hadn’t much of a life but, again, the older I get, the more untruth I find in that thought stream. Back in the mirror, I can see we are both men of the night and secretly smiling to ourselves. As time flies by, I am just beginning to dig into myself and discovering a lot of people in there.

Everyone called him The Manager, but no one knows why exactly. An irony, perhaps. He had twenty-eight acres of land in three parcels scattered around the village, and when he moved in with us, my father began farming the land alongside him.

At one time, The Manager lived and managed on his own, but an episode with a cigarette butt and flaming bed put an end to his bachelor living. Cattle and sheep were at ease in his company. On more than one occasion, I’d find one or other in his run-down bungalow front kitchen mooching around while he was brewing the tea. He’d spend hours sitting on his small front porch smoking, drinking tay, and pacing. Occasionally, slapping himself across the forehead and having mighty conversations with himself out loud. Brigid has caught me doing similar on one or two occasions driving the back-roads at night.

I consider him afresh tonight while watching the number of empty mugs mount on the back-kitchen windowsill of my own house, glancing up at the black sky, waiting for some moonlight to break through the cloud cover so that I might feel something and sit down and write about it in peace.

Once, when the school holidays kicked in and the first available stretch of good weather emerged, my old man always paired John and myself together to perform the big day-to-day summertime chores of a small breathing farm—the Clare man, like most Clare folk, a wild optimist. I remember a day saving the turf with John. The bog ritual involved an early morning dumping off on the bog road by my father on his way to work in the county council and collection in the evening on the return leg home—armed with his apology of cheeseburgers and chips.

Most of the time, I’d spend as much effort exploring the bog and the depths of the different bog holes as doing the actual manual labour of lifting sods of turf. After the obligatory hour of throwing shapes at the lines of never-ending brown sausage rolls in front of us, the two of us would stretch out on some bank of beaten-down heather smoking. Me, drinking gulps from a big bottle of TK red lemonade, and him slurping tea from a flask cup. I’d often have a paperback book or some comics stashed away somewhere on my person and lay back to read.

Sometimes, if Uncle John wasn’t too agitated with his nerves, he’d get relaxed enough from smoking and drinking tea to forget I was there and start talking to himself. He was funny, articulate, and animated in these unconscious, fully blown conversations. Like a different man altogether. Then, of course, he’d catch you looking at him, and his self-consciousness would return in an instant. The words dying suddenly on the bog breeze, frightened and vanished away.

His was a voice or sod trapped on the wrong bank of turf, you might say. So delicate and yet so dangerous too. We never found the right key to unlock his true voice. And sometimes you just don’t find it, I guess. Perhaps my mind is playing tricks, but odd characters were falling out of the hawthorn bushes in most Irish villages of the 1980s. Or so it seemed.

Our little townland had about fifteen houses, and at least five of those households were taken up with a category of person you don’t hear of anymore: confirmed bachelors. They were, one and all, various flavours of odd. Men who’d sworn off women, or more correctly, the type of man women left well enough alone.

If mental health had a business model back then, it came in the form of a threat to dissuade potential users of it. Families would endure all forms of mental anguish to avoid entrusting a loved one to the confines of the Irish mental health system. For in the West of Ireland, the system meant spending time in a mental hospital. And having a family member located, for any period of time, in a facility such as this was a label that stuck to a whole family.

“Be careful, or you’ll end up in Ballinasloe like The Manager ”

It was a brutal system, and our family felt the full force of its limitations with regard to our uncle. Yet poverty, or necessity, is indeed the mother of invention. The lack of resources forced communities to find a little elbow room for the differing colours in the rainbow of oddness surrounding them. The village understood my uncle and weren’t afraid of him, for he presented no physical threat. But if he ran out of cigarettes, it was not uncommon for us to find out the following morning that he’d traipsed down into the village at 2 am, banging down the door of one of the local shops in search of his next smoke.

People somehow found a way to tolerate this occasional inconvenience, by and large, because they knew we were doing our best. And by we, I mean my mother. Towns and villages were forced, through necessity, to be robust enough to cope.

It’s the fortunate family that isn’t hit with mental health issues of one type or another. In my own exposure to it in my family, lifelong mental illness is almost banal, such is the almost imperceptible trace of its progression. The most noticeable changes are often visible, most obviously, in the people that are in closest proximity to the sufferer rather than in the sufferer themselves. My uncle had a certain obliviousness to his own state. People dealing with these types of people often convince themselves they are above and beyond the reaches of its outstretched arms. My experience is that they most certainly are not.

I don’t know the answers even sitting here now, but I know it didn’t happen overnight or even over a specific series of them. The progression was much slower. I can’t quite place a time and date as to when these episodes, and others, turned from the almost silly, funny anecdotes of the momentarily forgetful to the roars of tortured anguish of the perpetually cursed.

But they did.

All I can say for certain is that it was the woman of the house that bore the deepest and most long-lasting scars. The person that bent the most to accommodate, at some point, struggled to stand fully upright. The decision to remove someone from your home for the overall well-being of the household is one of the hardest ones a family in these circumstances has to make. And I suppose the beauty and tragedy of Ireland back then is many homes couldn’t, or wouldn’t, bring themselves to make it. Call it empathy, sympathy, guilt, or some other emotion affiliated with caring too much. We couldn’t, and the hidden price of it was not small.

At what point were we a family that started hiding bread and tea bags in the washing machine at night?

And then, at what point after were we tragically unaware of hanging freshly washed, tea-stained jeans and the odd geansaí wetted by bread dough on the clothesline?

I don’t know.

Yet, I didn’t realise how much I loved him until tonight.

Chapter 10, Unvaxxed Soul

People in a particular place and time, looking out for each other, politics be damned, except politics is always around the corner, as a threat to our private and natural existence. You write so well about the private sphere, but it is now so encroached by the unpredictable and invasive public one that can not leave us to just be.

Thanks for letting your cyber family into the privacy of your real world.

Such examples are not uncommon, I too had an Irish Uncle who stayed with us in our home I'm England, my Mum was from Ireland.

Her brother, Paddy never got over the death of his younger brother, who was rumoured to be in the IRA..

He stayed with us off and on in between stays at the local mental hospital chain smoking his ciggies and playing his IRA records.

When we were getting to be an age when me and my sister needed our own rooms he had to leave and lived the rest of his days in a B and B run by an Irish lady whose business model was profit through state handouts from her lodgers.

While with us he'd disappear to the biggest town every so often on a Saturday to get drunk on Guinness or Mackeson and arrive back at ours drunk and disorderly. It was after one of these events that my Dad put his foot down and he had to leave.

Your poignant story brought back all the old memories and love I had for him. Thank you Gerry.